Feature Story

As published in the UConn Advance, March 12, 2007.

Growing Popularity of iPods Turns Up the Volume on Hearing Loss

By Carolyn Pennington

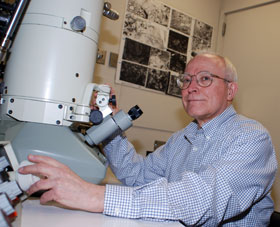

Dr. Kent Morest, a professor of neuroscience, uses an electron microscope to conduct research on hearing loss.

Photo by Frank Barton

You may not be surprised that a rock concert can cause partial hearing loss. But a tiny iPod seems much less threatening.

It may actually be more dangerous, however, according to Dr. Kent Morest, a professor of neuroscience at the Health Center, who specializes in hearing loss.

Research has found college students who listen to their iPods in a noisy environment tend to play them at 80 percent of the possible volume, putting their hearing at risk after a little more than an hour.

Other studies have found that due to loud music and a generally noisier environment, young people have a rate of impaired hearing two-and-a-half times that of their parents and grandparents.

For Morest, it doesn’t matter whether it’s an iPod or an old-fashioned Walkman, hearing loss simply depends on how loud the sound is and how long you’re exposed to it.

The louder the sound, the less time it takes to damage your ears.

Several NIH grants have helped Morest and his team of neuroscientists delve into the intricacies of hearing loss and they have come up with some disturbing findings.

For instance, they found that just a single exposure to a loud noise can cause permanent and progressive damage to a person’s hearing.

“The damage occurs in two places that we know of,” explains Morest.

“In the ear itself, where the tiny hair cells in the ear convert sound into electrical impulses, and in your brain, where it receives and processes the signals from the hair cells.”

But the really bad news is that the damage continues long after the noise is gone.

“It only takes one excessive exposure to cause a neurodegenerative disease in which synaptic endings continue to degenerate in the brain and the ear for years after a single exposure,” he says.

“This condition may account for the chronic, progressive nature of noise-induced hearing loss and tinnitus, which is ringing in the ears.”

Classifying noise-induced hearing loss as a neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s may seem unusual, but Morest says some of the same damaging mechanisms that lead to hearing loss may cause memory or motor skills loss in those diseases.

Unlocking the secrets to hearing impairment may someday offer clues in the treatment of Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, whose causes are unknown.

Although researchers know the major causes of hearing loss, there are no ideal treatments.

That’s why Morest and his team are experimenting with stem cells to help restore the hair cells in the ear that convert sound into electrical impulses.

They have been growing new hair cells and neurons (the nerve cells in the brain that receive the signals) in tissue cultures.

They’ve also started doing lab experiments where they have transplanted some of the cells and have found they can grow.

“Now we’re working to get them to not only grow, but to function as well,” says Morest.

His hope is that they can learn how to slow down the degenerative process and eventually stop the damage altogether.

In the past, requests for major funding for hearing research have often been ignored.

Morest says hearing is often considered to be a poor cousin of vision, and doesn’t have the life-or-death consequences of cancer or heart disease.

But the popularity of iPods has brought new attention to the issue of hearing loss, and the estimate that 50 million people in the U.S. will be hearing impaired by 2050 may finally get people to listen.