Feature Story

Health Center Today, August 14, 2009

Ugandan Health Clinic Thriving Thanks to UConn Medical School Volunteers

By Carolyn Pennington

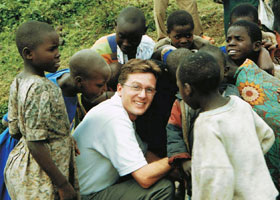

Kevin Dieckhaus shares a moment with some of the children near the clinic.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Dieckhaus

Here at the Health Center he is known as the chief of infectious diseases. In Uganda, he’s known as "Doctor Kevin." Kevin Dieckhaus has been making frequent trips to Uganda since 2003---volunteering his time and medical expertise to help build and manage a small clinic in a remote village. But it wasn’t until his most recent trip this summer that he really knew he was making a difference; one of the villagers, an elderly woman, approached him and said, “Welcome back, local man.”

The clinic is in Cyanika about 10 kilometers from the Democratic Republic of Congo and only half a kilometer from the Rwandan border. It took a few years to make the clinic a reality but now more than 50 patients are seen there every day.

The patients are treated for a variety of infectious diseases including malaria, HIV, parasites, respiratory and diarrheal illnesses, explains Dieckhaus. The clinic also provides pediatric immunizations for preventable childhood illnesses.

The idea for the hospital came from Bernadette Kazibwe, a native Ugandan who now lives in Colchester. She and her brother, Pius Bigirimana, founded the Clare Nsenga Foundation, raised the funds necessary to build the clinic, and convinced Dieckhaus to provide the medical-know-how to get it running. And every summer when Dieckhaus returns, he’s pleased to note that strides have been made.

For instance, they’ve hired another nurse so now there are three full-time nurses working in the clinic. Instead of relying on donations, day-to-day operating expenses are now covered by the Ugandan government. They have also invested in a propane powered refrigerator (the village has no electricity) which means they can store medications on-site including much-needed vaccines.

The health clinic is just the starting point for a whole network of programs that are improving life in the region and the University of Connecticut’s medical school students are an integral part of it. Over the past two summers, eight medical students or residents have accompanied "Dr. Kevin" to Uganda. "They see first-hand diseases that are rarely encountered here in the U.S. It’s an invaluable learning experience."

The villagers also benefit. The students go out in the community conducting health projects they’ve designed during the school year in Farmington. For example, one project involves students handing out mosquito netting to help cut down on malaria cases and then engaging the residents in a conversation about HIV. The students who return in the summer will continually assess how their efforts are making an impact in reducing malaria or HIV in the village.

Another program which has already made a significant impact is the AIDS orphan assistance program, funded by donors at the Asylum Hill Congregational Church in Hartford. The goal of the program is to keep children who have been orphaned by HIV/AIDS in school by supporting the purchase of school supplies and uniforms, payment of school fees, and supporting the families that have taken them in. There are an estimated 25,000 orphans living in the district, and not a single orphanage. Dieckhaus trained two people in the community who identify children eligible for the program and assess their families’ needs.

"This program has really blossomed," explains Dieckhaus. "Along with our efforts, nearly 100 parents have organized a group to do what they can to make sure orphaned children stay in school. The drop-out rate is horrendous, especially among girls, so this is really a positive step to see the school and parents step up and become involved."

Goats are another measure of progress. "We gave families who took in orphaned children goats to help support them. Now those goats have bred and their kids are being given to new families who are caring for orphaned children," explains Dieckhaus.

An HIV counseling and testing program continues with community workers and nurses at the clinic identifying those who should be tested. Test kits are also provided when health care workers are in the community offering prenatal care to villagers.

On a previous visit, Dieckhaus’ son Andrew, now 15, distributed more than 3,500 textbooks and reading books to local schools that had no reading materials. The books had been donated during book drives Andrew organized in his hometown. Now the village school has converted one of its rooms into a library which houses hundreds of donated books.

If that weren’t enough, a new project is underway - a job skills training program. They want to teach the girls how to sew and are in the process of providing sewing machines and other items to get them started.

They’re also planning for the future. The Clare Nsenga Foundation has bought the land behind the clinic so that some day it can expand and be more like a hospital where patients can stay overnight. "We started out with almost nothing," says Dieckhaus. "It’s very rewarding to see how much has been accomplished and how the lives of the villagers have been improved."