Feature Story

Health Center Today, April 21, 2010

In Pursuit of Promising Developments

By Stefanie Dion-Jones (first published in the Presidentís Annual Report 2010)

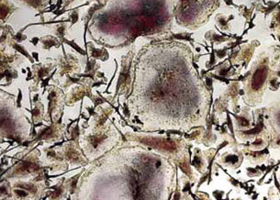

Root and her fellow researchers at the UConn Health Center use a stain to help identify human embryonic stem cells that are pluripotent, meaning they have the potential to differentiate into any cell type.

Photos from the Presidentís Annual Report 2010

Stem cells never cease to amaze Sierra Root, who has a particularly personal sense of dedication to spending day after day looking after, evaluating, and marveling at the cells she painstakingly cultivates in petri dishes at her UConn Health Center laboratory.

"The human body has over 200 cell types," Root says. "During development, you start with one cell type. Over nine months of pregnancy, you get a functional human being; itís amazing." Root arrived at UConn at a particularly opportune time, beginning her Ph.D. in biomedical sciences at the UConn Health Center in 2005. That same year, Connecticut became the third state in the nation to pass pioneering legislation providing public funding in support of stem cell research; the program pledged $100 million for stem cell research and training in Connecticut through the year 2015.

The potential of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) is exceedingly promising. These cells have the capacity to give rise to almost any type of specialized cell in the body. If scientists can determine how to control the differentiation of embryonic stem cells into specific types of cells Ė such as blood, bone, muscle, or virtually any other cell type Ė it could become possible to treat any number of diseases.

At first, Root wasnít certain that graduate students would be permitted to work firsthand with human embryonic stem cells. But shortly after arriving at UConn, she was conducting research alongside associate professor Ren-He Xu, an internationally recognized stem cell expert and director of the Stem Cell Core laboratory, established in 2006. Under Xu, Root became UConnís first graduate student to receive training in the complex methods required to grow and maintain hESCs.

In 2008, Root continued her stem cell research with H. Leonardo Aguila, an associate professor of immunology, director of the Flow Cytometry Core for Stem Cell Research, and one of several UConn faculty members working on a $3.5 million multi-investigator project headed by David Rowe, professor of genetics and developmental biology at the UConn Health Center.

According to Aguila, who also serves as Rootís advisor, the research taking place in his lab has taken a big step forward since Root joined the group. "We are now in a process in which we can feel extremely confident about how to maintain and grow embryonic stem cells, to differentiate them, to analyze them," he says. "We wouldnít be at that stage if Sierra hadnít joined our laboratory."

Osteoclasts, a type of bone cell, are important in bone formation and remodeling. Ph.D. student Sierra Rootís research relates in part to understanding the biological process that forms bone during development and identifying cells capable of ultimately developing into the precursors that form bone. Stem cell research in this area could one day help patients who suffer from such conditions as osteoporosis.

Combining the in-depth knowledge she acquired in Xuís lab and the expertise she is gaining now in cell analysis, Root is focusing her doctoral research on designing new strategies to generate, identify, and isolate specific cells that arise from hESCs and are capable of ultimately developing into the precursors Ėcalled progenitors Ė that form blood, bone, and blood vessels through biological processes called hematopoiesis, osteogenesis, and vasculogenesis. These three processes are tightly linked during development, and understanding how they interact could eventually benefit those diagnosed with such conditions as osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and several types of cancer.

Root has a special appreciation for the value of her research. Having endured a severe case of Lyme disease as a child and additional serious health problems as a young adult, she spent much of her teenage years either in the hospital undergoing surgery or at home, when she had no choice but to leave high school and be homeschooled. Always a strong student with diverse interests, she put her dreams of being a doctor on hold, knowing she wasnít well enough to leave home and attend college. She took a few community college courses in order to stay close to home and considered a possible technical career in radiology until one of her professors actively encouraged her to pursue a Ph.D.

Doctoral candidate Sierra Root, left, consults with her advisor, associate professor H. Leonardo Aguila, at the UConn Health Center.

The years she spent hospitalized as an adolescent left lasting memories. "Most of my hospitalizations as a kid were at a childrenís hospital in Philadelphia. I saw horrific, horrific things Ė just some really sad cases," she says. She remembers fellow patients suffering from sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, and various forms of cancer. "Stem cells are supposed to offer some promise for all of these diseases. So thatís definitely a motivation."

Though competition for stem cell research funding remains fierce, regulations have recently been eased by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) with the support of President Barack Obama, freeing up federal money for human stem cell research efforts. "I think itís very important that we work together as a team," Root says. "With stem cell research, itís not one lab or one person thatís going to make a difference. Itís going to take some time ... and thereís still a lot to overcome."